Friday, August 19, 2022

Another perspective on Fort Laramie

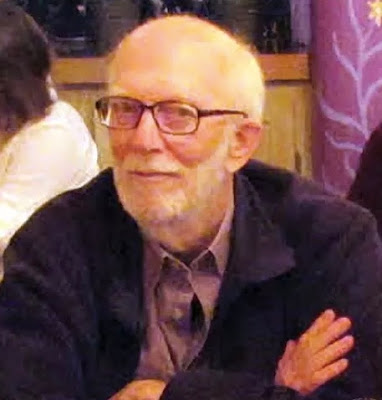

Below is a long article well worth the time needed to read it. It was written by Richard West Sellars, an historian who worked for the National Park Service for 35 years, but in this article criticizes the way the NPS presents history at Fort Laramie N.H.S. He obviously is not a native American author, but he takes seriously their concerns. It may or may not be significant that Sellars wrote this article after he had retired from the Park Service! I'm still looking for an article by a contemporary tribal member which critiques Fort Laramie N.H.S. Here is a tribute to Sellars at the time of his death a few years ago:

"The National Park Service and its huge family of partners, supporters, fans, and alumni lost an important and influential figure on 1 November 2017 in the death of Richard West Sellars, NPS historian, author, lecturer, and courageous student of NPS policy archives. He lived in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and was 81 years old.

Sellars began his career with the National Park Service in 1966 as a seasonal ranger-naturalist at Grand Teton National Park. He then pursued a PhD in American history at the University of Missouri–Columbia, which he completed in 1972. He returned to the NPS in 1973 in Denver, often teaching staff how to manage historic sites. From 1979 to 1988 he served as the Southwest Regional chief of historic preservation, architecture, and archaeology and also oversaw a Service-wide program in underwater archeology.

In 1989 he began an eight-year period devoted to researching the history of NPS natural resource management, which led to publication of his 1997 landmark book, Preserving Nature in the National Parks: A History. According to a 2012 High Country News article profiling Sellars, the work “charted the influence of agency administrators and landscape architects, whose tourism-driven agenda often eclipsed biologists’ efforts to preserve ecological health.” Reaction to the book ranged from widespread praise for focusing attention on the erratic development of natural resource management policy in the context of overall NPS policy to criticism as revisionist history that demonized past policies for making parks accessible.

The effect of the book was tremendous and immediate, elevating the need for science-based natural resource management to a high priority alongside NPS staples of serving and protecting visitors. By 1999, the National Park Service had announced its Natural Resource Challenge initiative, and over the next several years greatly increased the number of new scientific staff working for the bureau in parks, at 32 park networks, and at regional and national offices, all in support of meeting park science needs.

Sellars is the recipient of several top honors for his long-term contributions to the National Park Service and resource conservation: the Department of the Interior’s Meritorious Service Award, the Coalition of National Park Service Retirees’ George B. Hartzog Award, and the George Wright Society’s George Melendez Wright Award for Excellence.

He retired from the National Park Service in 2008. Over his 35-year NPS career he influenced and educated many people through his historical research, writing, lecturing, and teaching, and challenges to NPS traditions."

Richard West Sellars (1936-2017)******************************

The Truth Lies Buried at Fort Laramie by RICHARD WEST SELLARS. This article was originally written June 8, 2011 and was updated Sept. 13, 2018.**************************

"Driving my VW Bug along Interstate 70 in early January 1973, I was crossing the wide Missouri and on to Denver to report for work as a historian with the National Park Service. With both a degree and employment in hand, and aware that the academic job market for historians had crashed, I felt extremely lucky.

My first field assignment was to prepare a report on the Fort Laramie National Historic Site in southeastern Wyoming. Although inexperienced in Park Service practices, I drove up to the fort hoping to learn what preservation at a historical park was all about. It was not what I expected.

I arrived at the entrance to the park just after opening time on a mild mid-January day and encountered a grim, tense park official with a high-powered rifle and holstered pistol—the fort was locked down! Guarding the closed entrance gate, he informed me that AIM (American Indian Movement) had threatened to burn down Fort Laramie. Alarmed by the threat, the superintendent had closed the fort for the day as federal law-enforcement officers rushed to the park from duty stations in the general area.

Fort Laramie dates from the 1830s, when many promoted America’s conquest of the West as the nation’s “Manifest Destiny,” ordained by Providence. The fort is located along the Laramie River, near where it joins a much larger river, the North Platte—waters that flow through the Northern Plains—high, open grasslands stretching from about northeastern Colorado and northwestern Kansas all the way into Canada. It seemed strange that AIM had targeted this isolated, historic military post, but the park’s defensive response was not without justification, as AIM had already confronted the National Park Service, demonstrating at Mount Rushmore National Memorial in South Dakota’s Black Hills, where it viewed the memorial’s gigantic, sculpted presidential heads as symbols of pernicious government policies, past and present. The government’s violation of agreements made at Fort Laramie in the late 1860s constituted a primary motive behind AIM’s protests, and its focus on the fort effectively put to test the National Park Service’s willingness to adapt to changing times—to address historical questions at the park arising from darker, more inclusive perspectives on the United States’s occupation of the West.

The Unvarnished History of the Great Sioux War

Knowing only the general outlines of the fort’s history, or that of the Northern Plains, I arrived at Fort Laramie nearly 140 years after mountain men established a fur-trading post in the vicinity in 1834. It developed into an important center where the Lakota Sioux, along with the Northern Cheyenne and Northern Arapaho, among other free-roaming tribes, came to barter furs and buffalo hides for trade goods. And by the time the U.S. Army acquired Fort Laramie in 1849, it had also become an important way station along the Oregon and California trails, and the Mormon Trail to Utah—routes traveled each year by thousands of emigrants. Their presence antagonized the Indians, resulting in occasional attacks on overland travelers. Army activity at Fort Laramie and across the Northern Plains proved fateful for the Native tribes, with two major treaties, two wars and the decisive loss of a way of life. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 sought to reduce armed conflict between Indians and whites, offering annuities as well as curbs on white encroachment in return for Indian guarantees to let whites travel along the trails to points farther west. It also sought to rein in intertribal territorial feuding by keeping tribes more-or-less separated, with each to occupy a designated area—a precursor to reservations. But many Indians and whites deemed the treaty unsatisfactory.

In late November 1864, along Sand Creek in eastern Colorado Territory, U.S. volunteer troops massacred at least 165 Cheyenne and Arapaho men, women and children, heightening Indian resentment of whites all across the plains. Tension reached a danger point along the Bozeman Trail, which crossed through tribal hunting grounds northwest of Fort Laramie in the Powder River country and connected the Oregon Trail to gold fields in today’s southwestern Montana. In 1866, the steady flow of whites along the Bozeman Trail, protected by three newly erected military posts, helped precipitate Red Cloud’s War, named after the great Lakota leader. Unable to defeat the Indians, the army ultimately pulled back and negotiated the all-important Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868—a source of antagonism even today.

Meeting with Indians at Fort Laramie, government negotiators led by William Tecumseh Sherman (soon to be named Commanding General of the United States Army) agreed to abandon the Bozeman Trail and the new forts, leaving the Powder River country of Wyoming and Montana as Indian hunting territory. Of special consequence, the treaty established the Great Sioux Reservation covering all of present-day South Dakota lying west of the Missouri River, and including the Black Hills plus a small part of North Dakota. Yet the “non-treaty” Indians under such leaders as Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse rejected the treaty, determined to protect their lifeways and opposed to restrictions on hunting areas and to living on reservations—a portent of more warfare.

White intrusion on to Indian lands (particularly in search of gold in the Black Hills) and the non-treaty Indians’ continued resistance triggered another conflict: the Great Sioux War, beginning early in 1876. Mainly fierce, intermittent pitched battles (the defeat of Custer’s Seventh Cavalry along the Little Bighorn River being the most well-known), the war lasted into 1877. At the end, and in contradiction to terms of the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, the Sioux lost the Black Hills through manipulative pressure by top-level military and political leaders, backed up by the U.S. Congress. By the early 1880s white market-hunters were obliterating the buffalo herds, and within the next decade the Indians lost much more of their reservation lands.

In 1890 the army pulled out of Fort Laramie, and left about 60 standing buildings to be sold at public auction. The state of Wyoming purchased the fort in 1937 and donated it to the National Park Service the following year. By the early 1960s Fort Laramie National Historic Site had begun receiving large numbers of visitors curious about the history of the westward movement.

Listening to What’s Not Being Said

As I was preparing to write these comments about Fort Laramie, I was in the general area more than once, and each time took the opportunity to revisit the fort and consider more closely the stories it tells the public. And the closer I examined the park the more I questioned how the service had treated the fort’s historic buildings and interpreted its history. For sure, had AIM leaders actually shown up and bothered to take the ranger-led tour of the fort, they would have been even more irritated. As just one example, visitors who take the current tour are told about the army’s installation of birdbaths and indoor plumbing in the 1880s, but no mention is made of the army’s impact on Indian life-ways, on their tribal culture and independence.

In 1987, roughly 14 years after AIM’s initial threat, the park completed its last, and one of its most ambitious, restoration efforts, affecting about half of the two-story, 273-foot-long enlisted men’s cavalry barracks. Of the half-dozen or more army buildings restored by the Park Service, it is this structure that most symbolizes the military’s final, determined drive to subdue the Indians—in current lingo, its “shock and awe” against Northern Plains tribes. The army had built the barracks in 1873-1874 to accommodate a hundred or more additional cavalrymen, thereby strengthening its mounted forces to strike the enemy: those Indians who refused to accept confinement on their reservation or abandonment of traditional hunting areas.

But what one sees today in the barracks is mainly where the soldiers ate and slept. The ultimate purpose of the 1870s cavalry barracks—to house reinforcements for the final suppression of Northern Plains Indians to make way for white occupation—is only implied. Overall, the messages conveyed by Fort Laramie’s restored buildings, and most notably at the cavalry barracks, reveal no substantive connection with consequences of the army’s military actions on the plains.

It is a mystery to me why daily army life should be presented as the primary aspect of the site’s history, and it suggests the need for the Park Service to print the disturbing facts as much if not more than it prints the romantic legend. Otherwise, where and how does the Indian story fit in? They suffered the worst consequences. And without their presence, the military would have had little need to build forts on the Northern Plains.

History Noir

Nearly four decades after AIM made clear its feelings about the fort, the park’s story is still revealing—for what it says as well as for what is it does not say about the fort’s history and legacy. The park brochure describes Fort Laramie as having been an “important supply and communications center” and a “major staging and logistical center” during the campaigns against the Plains Indians. Certainly this was the case. But surely, most of the truly consequential actions of the Fort Laramie garrison came after the soldiers received orders from the commanding officer and rode out across the plains, possibly to fight and die in combat with American Indians.

Troops coming out of Fort Laramie participated in the Great Sioux War of 1876-1877, seeking to force non-treaty Indians onto their reservation, and fighting at Powder River, Rosebud Creek and Slim Buttes—but not at the Little Bighorn. It is estimated that about two-fifths of the entire U.S. Army served on the Northern Plains at the height of the Great Sioux War. And of those soldiers not stationed at Fort Laramie, many stopped at the fort for rest and replenishment.

Aided by its bases at Fort Laramie and elsewhere, the military effectively concluded the Great Sioux War by the summer of 1877. During the conflict, both General Sherman and especially his subordinate (and successor), General Phil Sheridan condoned a kind of total war against the Plains Indians, somewhat akin to their Civil War strategies that had devastating effects in Georgia and the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. The generals viewed the mass slaughter of buffalo as a convenient means to complete the destruction of the tribes’ most crucial food source—in effect, an early take on biological warfare.

The park’s “official” story gives only brief references to the military’s failure to steadfastly defend treaty-guaranteed Indian land rights against white incursion. Surely the most notorious failure was the aborted effort to protect Sioux tribal rights once the Black Hills gold rush began in 1874-1875. In a matter-of-fact way, park interpretation comments that “little effort was made” to prevent whites from entering the Black Hills, but avoids any mention of the sleight-of-hand calculations made at the nation’s highest political and military levels to take that land from the Indians. And in an example of what I think of as “drive-by” interpretation, a park audio-tour comments briefly on the Indians’ refusal to sell the Black Hills, and the coming of the Sioux War—but quickly turns sentimental, and the visitor hears (along with background music) an army wife’s wistful recollection of the military band playing “The Girl I Left Behind Me” as the men rode off from the fort in 1876 to do battle against the tribes.

Conspicuously missing from the park’s story are the perpetual disputes over the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 that have lasted to the present day. After the Indians had won decisively at Little Bighorn, but suffered defeat elsewhere, an official delegation from Washington coerced the Lakota into an “agreement” giving up their rights to the Black Hills portion of their reservation—lands the 1868 treaty had guaranteed them. Threatening to withhold food rations, the delegation used a sign-or-starve ploy to force tribal acquiescence. Although park interpretation mentions the Black Hills at times, it avoids any clear indication that the government grabbed this land back from the Lakota.

Negotiations for that 1868 treaty took place at Fort Laramie, and without doubt comprised the single most important historical occurrence at the fort. But the Park Service makes no effort to inform the public that the treaty remains a living, festering source of contention—as is evidenced by AIM’s threats against the very site where the treaty was negotiated, and by the still unresolved Sioux litigation over the Black Hills.

With so many Indians forced onto reservations and buffalo reduced almost to extinction so that they no longer threatened to stampede through farmsteads or cattle ranches, most of the Northern Plains were left open for white settlement. The Fort Laramie museum exhibit text notes that white settlers “made their homes on former Indian lands, and ranchers acquired great expanses of territory, where cattle replaced the buffalo.” The text also recalls the defeat of the tribes in the 1870s, and states that they became “starving, ragtag refugees and prisoners in their own land.” Of all the interpretive statements in the park, this brief, disparaging comment may well provide the most explicit acknowledgement that Fort Laramie’s military history had any enduring tragic consequences.

The museum exhibit text and film briefly cover the long period of white civilian use of the old fort after the army left in 1890, but they give little indication of the long-term fate of American Indians who once roamed throughout the area. Yet even while the army still occupied Fort Laramie and the tribes were taking refuge on the reservations, the Indians’ “own land,” in which they were said to be prisoners, had begun to shrink.

In 1887, Congress passed the General Allotment Act, mandating processes by which tribal ownership of reservation lands could be replaced by private, individual Indian ownership, a practice known as “allotment in severalty.” The policies were intended to convert the tribesmen into farmers and ranchers, much like whites, but they also left the Indians vulnerable to fraudulent manipulation by the government and private sectors, and many inexperienced allottees sold their lands to whites.

Assaulted by other government assimilation measures, such as intense pressure to convert to Christianity and forced attendance at Indian schools that required students to speak English language only, tribal reservation life came to include high rates of unemployment, poverty and alcoholism. Persistent racial discrimination fueled these and other consequences, which have affected generations of Indians to this day. Yet today’s visitor at Fort Laramie could take the complete historic buildings tour and go home with little knowledge about the grim consequences of the wars against the Northern Plains tribes.

War and the Remembrance of War Can Be Addictive

The one serious attempt to connect Fort Laramie’s interpretation with current Western history scholarship was initiated in the mid-1990s by Bill Gwaltney, park superintendent at the time. He began by going to the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation to, as he told me, “broker a better relationship” with the Lakota. He then hosted Indian activists and other concerned individuals at the park for a discussion of the fort’s history and interpretation.

Gwaltney’s efforts failed outright. Confronted with possible changes to the park’s Manifest Destiny interpretation, both the Fort Laramie staff and local area residents resisted. Gwaltney recently told me that some staff seemed to think it was “almost politically dangerous to know too much about Indians.”

If war is an addiction, as has been said, so too can the remembrance of war be addictive—and the threat to entrenched local perceptions of Fort Laramie’s history triggered the protective response of a mother hen. But national parks belong to the nation as a whole: Citizens who live near Fort Laramie have a stake in Park Service–administered Ellis Island or Yosemite, whether or not they have ever been there. And likewise, residents of New York or California have a voice in Fort Laramie’s management, if they wish.

But even the Park Service’s Denver Office did not override local and staff resistance and force the proposed interpretive changes—further evidence of National Park Service corporate culture’s tendency to adhere to the status quo. It seems the Service did not understand the need to understand.

In late 2010, the service announced the park’s online virtual tour of the fort, which of course puts Fort Laramie’s history in easy reach of a vast new audience. However, this high-tech presentation makes no effort to rethink the fort’s past and address the overall impact of the military on the Northern Plains Indians.

In contrast to Fort Laramie, extraordinary changes in interpretation have taken place at some long-established parks, such as at Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument in Montana, which preserves “Last Stand Hill” and surrounding lands that have been a Custer shrine since almost immediately after the June 1876 battle. Indications of contested history at the site had emerged periodically in the past—but it was none other than AIM, through its dramatic, intimidating protests at the battlefield in 1976 and 1988 that provided the key impetus for change.

Amid much controversy, Congress reacted in 1991 by rescinding the park’s decades-old designation, “Custer Battlefield,” a name offensive to many Indians, particularly descendants of those who won the battle. Congress also authorized an Indian memorial at the park to honor those who fought there to defend their way of life. After some hesitation, the National Park Service actively supported the changes, and began promoting Indian participation in ceremonies at the battlefield and including them in park management and staffing.

Unlike present-day Little Bighorn, with its much expanded attention to the Indian perspective, Fort Laramie does not in any way qualify as one of what I believe can rightly be called “atonement sites” within the national park system—places that, through forthright interpretation, make meaningful acknowledgement of the more troubling aspects of America’s historic past, and of public regret. Park Service experience with atonement sites has grown in recent decades, such as at the Sand Creek Massacre site in eastern Colorado. Another, Washita Battlefield National Historic Site in far-western Oklahoma, preserves the setting of a bloody attack by Custer’s Seventh Cavalry in November 1868 on Chief Black Kettle’s band of Cheyenne. Washita, with its newly constructed visitor center and interpretive trails, provides an example of fair and equitable interpretation at a site of deeply painful history—it shows how much the Service can do when working openly and candidly with historical data and all affected parties. Sand Creek’s interpretation, still in preparation, seems on track for similar results.

Recently (and as required from all parks by the Washington office), Fort Laramie submitted a plan to commemorate the National Park Service Centennial in 2016; and among other items it calls for creating an on-site Northern Plains Treaty Center—a nod in the direction of atonement. There, presumably, different views of the fort’s history would be open to analysis. What could attract visitors more than exhibits that fully address the controversial issues of Fort Laramie’s historic past?

In fact, the centennial plan seeks to encourage more Indians to visit the park and to “provide interpretive services.” But both of these goals seem out of reach, given the general drift of the centennial plan.

Manifest Destiny and the Artful Dodger

In a phrase that appears to be almost obligatory at Park Service Manifest Destiny sites, Fort Laramie’s interpretation refers to the epic conflict in the West between whites and Indians as a “clash of cultures.” True in many respects, yet the phrase seems much too benign, as it leaves open the possibility—it almost suggests—that the clash was somewhat evenly matched, which it was not. (I doubt if that phase appears much, if at all, in parks that interpret white treatment of African Americans.)

In reality, the whites were the aggressive new superpower on the Northern Plains, and if the Indians thought there was a limitless flow of emigrants crossing the plains and spreading out from the Rockies to the West Coast, one could argue that they were right: It is still going on, but from all directions and by whatever means (including in a VW Bug loaded with academic books). In the history profession, assertions of inevitability generally get a negative reception. But given the way Indians had already been treated in the East, South and Midwest, it seems to me that there was a certain inevitability that the whites, with their numbers and their might, would in time subjugate the Northern Plains tribes and take their lands, and that the tribes would be forced to endure a tragic aftermath. What else should one expect? (Even today, some may call this Manifest Destiny, but its true name is American Imperialism.) And sooner or later, descendants of the empire builders would surely want to commemorate their conquests by preserving celebratory places like Fort Laramie.

So it may come as no surprise that the National Park Service has played the role of an Artful Dodger at the fort, a court historian skewing the story to avoid history’s darker aspects. Tracking the Service through a 35-year career, I know for sure that it has played an Artful Dodger elsewhere, although less so now than in years past. Still, it is time to shed that role at Fort Laramie—and wherever else similar problems exist in the national park system.

Editor’s Note: If you would like to encourage the National Park Service to improve its telling of Indian history at Fort Laramie—or at any of the other national parks—contact the superintendent in charge of that park here, or you can contact the NPS Director’s office in Washington, D.C. at Jon_Jarvis@nps.gov."

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment